| American comics | |

| File:NESteamrollers3.gif | |

| caption | |

| alt | |

| date | c.1842 on |

| pub# | |

| title# | |

| person# | |

| series# | |

| character# | |

| lang1 | English |

| related# | |

| Culture of the United States |

|---|

Architecture |

An American comic book is a small magazine originating in the United States and containing a narrative in the form of comics. Since 1975 the dimensions have standardized at 6 ⅝" x 10 ¼" (17 x 26 cm), down from 6 ¾" x 10 ¼" in the Silver Age, although larger formats appeared in the past.

Since the invention of the modern comic-book format in 1933,[1] the United States has produced the most examples, with only the British comic books (during the inter-war period and up until the 1970s), the Italian ones, called by them fumetti and the Japanese manga as close competitors in terms of quantity.[citation needed]

Sales of comic books began to decline after World War II, when the medium had to face competition with the spread of television and mass-market paperback books. Confirming the trend, mass-media researchers in the period found comic-book reading among children with television sets in homes "drastically reduced".[2] In the 1960s, comic books' audience expanded to include college students who favored the naturalistic, "superheroes in the real world" trend initiated by Stan Lee at Marvel Comics. The 1960s also saw the advent of the underground comics. Later, the recognition of the comic medium among academics, literary critics and art museums helped solidify comics as a serious artform with established traditions, stylistic conventions, and artistic evolution.

History[]

Proto-comic books and the Platinum Age[]

The development of the modern American comic book happened in stages. Publishers had collected comic strips in hardcover book form as early as 1833, with The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck, which appeared in New York in 1842, as the first example published in English.[1]

The Yellow Kid in McFadden's Flats (1897). The Yellow Kid did not speak; messages in a pidgin vernacular appeared on his nightshirt. This message reads: "Dis book is de story of me sweet young life".

The G. W. Dillingham Company published the first known proto-comic-book magazine in the U.S., The Yellow Kid in McFadden's Flats, in 1897. It reprinted material – primarily the October 18, 1896 to January 10, 1897 sequence titled "McFadden's Row of Flats" – from cartoonist Richard F. Outcault's newspaper comic strip Hogan's Alley, starring a character called the Yellow Kid. The 196-page, square-bound, black-and-white publication, which also includes introductory text by E. W. Townsend, measured 5x7 inches and sold for 50 cents. The neologism "comic book" appears on the back cover.[1] Despite the publication of a series of related Hearst comics soon afterward (including the first known full-color comic, The Blackberries, in 1901) the first monthly comic book, Comics Monthly) did not appear until 1922 and only lasted a year. Produced in an 8½-by-9-inch format, it reprinted newspaper comic strips.[1]

The Funnies and Funnies on Parade[]

In 1929 Dell Publishing (founded by George T. Delacorte Jr.) published The Funnies, described by the Library of Congress as "a short-lived newspaper tabloid insert".[3] (not to be confused with Dell's later comic book of the same name, which began publication in 1936.) Historian Ron Goulart describes the 16-page, four-color periodical as "more a Sunday comic section without the rest of the newspaper than a true comic book. But it did offer all original material and was sold on newsstands".[4] The Funnies ran for 36 issues, published Saturdays through October 16, 1930.

In 1933, salesperson Maxwell Gaines, sales manager Harry I. Wildenberg, and owner George Janosik of the Waterbury, Connecticut company Eastern Color Printing – which (among other things) printed Sunday-paper comic-strip sections – produced Funnies on Parade as a way to keep their presses running. Like The Funnies but only eight pages long,[5] this appeared as a newsprint magazine. Rather than using original material, however, it reprinted in color several comic strips licensed from the McNaught Syndicate and the McClure Syndicate. These included such popular strips as cartoonist Al Smith's Mutt and Jeff, Ham Fisher's Joe Palooka, and Percy Crosby's Skippy. Eastern Color neither sold this periodical nor made it available on newsstands, but rather sent it out free as a promotional item to consumers who mailed in coupons clipped from Procter & Gamble soap and toiletries products. The company printed ten-thousand copies.[5] The promotion proved a success, and Eastern Color that year produced similar periodicals for Canada Dry soft drinks, Kinney Shoes, Wheatena cereal and others, with print runs of from 100,000 to 250,000.[4]

Famous Funnies and New Fun[]

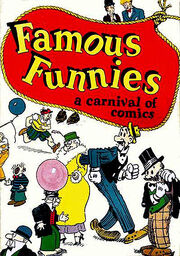

Eastern Color Press' Famous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics (Eastern Color Printing, 1933)

Also in 1933 Gaines and Wildenberg collaborated with Dell to publish the 36-page Famous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics,[6] which historians consider the first true American comic book; Goulart, for example, calls it "the cornerstone for one of the most lucrative branches of magazine publishing".[4] Distribution took place through the Woolworth's department-store chain, though it remains unclear whether it was sold or given away; the cover displays no price, but Goulart refers, either metaphorically or literally, to "sticking a ten-cent pricetag [sic] on the comic books".[4]

When Delacorte declined to continue with Famous Funnies: A Carnival of Comics, Eastern Color on its own published Famous Funnies #1 (cover-dated July 1934), a 68-page giant selling for 10¢. Distributed to newsstands by the mammoth American News Company, it proved a hit with readers during the cash-strapped Great Depression, selling 90 percent of its 200,000 print — though putting Eastern Color more than $4,000 in the red.[4] That quickly changed, with the book turning a $30,000 profit each issue starting with #12.[4] Famous Funnies would eventually run 218 issues, inspire imitators, and largely launch a new mass medium.

Famous Funnies #1 (July 1934). Cover art by Jon Mayes.

When the supply of available existing comic strips began to dwindle, early comic books began to include a small amount of new, original material in comic-strip format. Inevitably, a comic book of all-original material, with no comic-strip reprints, debuted. Fledgling publisher Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson founded National Allied Publications – which would evolve into DC Comics – to release New Fun #1 (Feb. 1935). This came out as a tabloid-sized, 10-inch by 15-inch, 36-page magazine with a card-stock, non-glossy cover. An anthology, it mixed humor features such as the funny animal comic "Pelion and Ossa" and the college-set "Jigger and Ginger" with such dramatic fare as the Western strip "Jack Woods" and the "yellow-peril" adventure "Barry O'Neill", featuring a Fu Manchu-styled villain, Fang Gow. Issue #6 (Oct. 1935) brought the comic-book debut of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the future creators of Superman, who began their careers with the musketeer swashbuckler "Henri Duval" (doing the first two installments before turning it over to others) and, under the pseudonyms "Leger and Reuths", the supernatural-crimefighter adventure Doctor Occult.

Superheroes and the Golden Age[]

- Main article: Golden Age of Comic Books

In 1938, after Wheeler-Nicholson's partner Harry Donenfeld had ousted him, National Allied editor Vin Sullivan pulled a Siegel/Shuster creation from the slush pile and used it as the cover feature (but only as a backup story)[7] in Action Comics #1 (June 1938). The duo's alien hero, Superman, dressed in colorful tights and a cape evoking costumed circus daredevil performers, became the archetype of the "superheroes" that would follow. Action would become the American comic book with the second-largest number of issues, next to Dell Comics' Four Color, with over 860 issues published Template:As of.

Action Comics #1 (June 1938). The debut of Superman. Cover art by Joe Shuster.

Siegel and Shuster's Superman, influenced by the pulp fiction stories and by the legend of the Golem of Prague,[citation needed]

had superhuman strength, speed and other abilities, and lived day-to-day in his secret identity as a mild-mannered reporter named Clark Kent. Within two years, most comic-book companies had started publishing large lines of superhero titles, and Superman has gone on to become one of the world's most recognizable characters.

Aficionados know the period from the late 1930s through roughly the end of the 1940s as the Golden Age of comic books. It featured extremely large print-runs, with Action and Captain Marvel selling over half a million copies a month each;[8] comics provided very popular cheap entertainment during World War II, but erratic quality in stories, in art, and in printing. Unusually, the comics industry provided jobs to an ethnic cross-section of Americans (particularly Jews), albeit often at low wages and in sweatshop working-conditions.

Following World War II the popularity of superhero comics rapidly declined. Publishers began to phase them out around 1945 and replace them with teen humor (epitomized by Archie Comics), funny animal comics (such as those featuring Walt Disney characters), science fiction, Western, romance, and satire comics. Timely's superhero line ended in 1950 when it canceled Captain America, which had already been converted into a horror title for its final issues. Except for National's Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, superheroes practically went extinct by 1952.

Comics as an overall genre continued to increase their readership into the 1950s, however, with Walt Disney's Comics and Stories selling almost three million copies a month in 1953).[9] Close to a dozen Dell funny-animal titles sold over one million copies each per month. EC Comics' more adult-oriented horror titles sold 400,000 a month.[citation needed]

The Comics Code[]

- Main article: Comics Code Authority

In the late 1940s and early 1950s horror and true-crime comics flourished, many containing violence and gore. EC ("Educational Comics", later renamed "Entertaining Comics") owned by Max Gaines' son, William M. Gaines, became the most successful and artistically creative of all the publishers. The careers of many famous artists such as Al Feldstein, Wallace Wood, Reed Crandall, Jack Davis, Will Elder and others began in the offices of EC. However, in spite of the quality of the work, psychiatrist Fredric Wertham singled out Gaines (unjustly[citation needed] ) as the most infamous of the comic moguls.

Wertham's book Seduction of the Innocent (1954), concerned with what he perceived as sadistic and homosexual undertones in horror comics and in superhero comics respectively, raised public anxiety about comics. Soon moral crusaders blamed comic books as a cause of poor grades, juvenile delinquency, drug use, and ultimately, "crime" itself.[10] This led the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency to take an interest in comic books (April–June, 1954). As a result of fiery debates[citation needed]

and irrational actions[citation needed]

, schools and parent groups held public comic-book burnings, and some cities banned comic books. Industry circulation declined drastically.

In the wake of these events, many comics publishers, most notably National and Archie, founded the Comics Code Authority in 1954 and drafted the Comics Code, intended as "the most stringent code in existence for any communications media".[citation needed]

A Comic Code Seal of Approval soon appeared on virtually every comic book carried on newsstands. EC, after experimenting with less controversial comic books, dropped its comics line to focus on the satiric Mad — a comic book that changed to magazine format in order to circumvent the Code.

Silver Age of Comic Books[]

- Main article: Silver Age of Comic Books

Showcase #4 (Oct. 1956), the launch of comics' Silver Age. Cover art by Carmine Infantino and Joe Kubert.

The Silver Age represents the period in which superheroes returned and came to dominate the comic book lines of the two major publishers, Marvel and DC. In the mid-1950s, following the popularity of the television series The Adventures of Superman, publishers experimented with the superhero once more. Showcase #4 (National, 1956) re-introduced The Flash and began a second wave of superhero popularity that became known as the Silver Age. National expanded its line of superheroes over the next six years, introducing new versions of Green Lantern, the Atom, Hawkman, and others.

In 1961 writer/editor Stan Lee and artist/co-plotter Jack Kirby created the Fantastic Four for Marvel Comics. With an innovation that changed the comic-book industry, The Fantastic Four #1 initiated a naturalistic style of superheroes with human failings, fears, and inner demons - heroes who squabbled and worried about the likes of rent-money. In contrast to the super-heroic do-gooder archetypes of established superheroes at the time, this ushered in a revolution. With dynamic artwork by Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, and others complementing Lee's colorful, catchy prose, the new style found an audience among children (who loved the superheroes) and college students (who claimed to find deeper themes). Marvel was initially restricted in the number of titles it could produce in that its books were distributed by rival National, a situation not alleviated until the late 1960s.

Other notable companies included the American Comics Group (ACG), the low-budget Charlton, where many professionals such as Dick Giordano got their start; Dell; Gold Key; Harvey Comics, home of the Harvey cartoon-characters (Casper the Friendly Ghost) and non-animated others (Richie Rich); and Tower, best-known for T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents.

Underground comics[]

During the late 1960s and early 1970s a surge of underground comics occurred. These comics, published independently of the established comic-book publishers, mostly reflected the youth counterculture and drug culture of the time. Many featured an uninhibited, irreverent style, which hadn't been seen in comics before. The movement is often considered[citation needed]

to have been started by R. Crumb's publication of Zap Comix #1 in 1968, though there were antecedents such as pornographic "Tijuana bibles", dating to the 1920s, and Frank Stack's The Adventures of Jesus, published in 1962.

Although many of the underground artists continued to produce work, most historiansTemplate:Who regard the underground comix movement as having ended by 1980, to be replaced that decade by a rise in independent, non-Comics Code compliant alternative comics and the resulting increase in acceptance of adult-oriented comic books.

Bronze Age of Comic Books[]

- Main article: Bronze Age of Comic Books

Wizard originally used the phrase "Bronze Age" in 1995 to denote the Modern Horror age. But Template:As of historians and fans use "Bronze Age" to describe the period of American mainstream comics history that begins with a period of concentrated changes to comic books circa 1970. Unlike the Golden/Silver Age transition, the Silver/Bronze transition involved many continually published books, making the transition less sharp; not every book entered the Bronze Age at the same time.[11]

Changes commonly considered[citation needed]

to mark the transition between Silver and Bronze ages include:

- A reshuffling of popular creators, including the retirement of Mort Weisinger, editor of the Superman books, and the movement of Jack Kirby to DC.

- A boom in non-superhero and borderline superhero comics such as Conan the Barbarian, Tomb of Dracula, Kamandi, Swamp Thing, Man-Thing, Ghost Rider, and the revived Doctor Strange and Phantom Stranger.

- "Relevant" comics which attempted to address serious social issues, such as the drug-abuse issues of The Amazing Spider-Man and Green Lantern/Green Arrow.

- The Comics Code Authority's first update, in 1971 — prompted by Stan Lee's defiance of the code for a story on narcotics at the behest of the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

- Revamping of several popular characters, including a "darker" Batman closer to the original 1930s conception, several changes to Superman such as the disappearance of Kryptonite, and a temporary non-powered era for Wonder Woman.

- The death of major characters such as Spider-Man's girlfriend Gwen Stacy, the Doom Patrol, and several members of the Legion of Super-Heroes.

The Modern Age[]

- Main article: Modern Age of Comic Books

The development of a non-returnable "direct market" distribution system in the 1970s coincided with the appearance of comic-book specialty stores across North America. These specialty stores were a haven for more distinct voices and stories, but they also marginalized comics in the public eye. Serialized comic stories became longer and more complex, requiring readers to buy more issues to finish a story. Between 1970 and 1990, comic-book prices rose sharply because of a combination of factors: a nationwide paper shortage, increasing production values, and the minimal profit incentive for stores to stock comic books (due to the small unit price of an individual comic book relative to a magazine).

Spawn #1 (May 1992). Cover art by Todd McFarlane.

In the mid-to-late 1980s, two series published by DC Comics, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, had a profound impact upon the American comic-book industry. Their popularity and the mainstream media attention they garnered, combined with changing social tastes, led to a more mature-themed, darker tone nicknamed by fans as "grim-and-gritty".[citation needed]

The growing popularity of antiheroes such as the Punisher and Wolverine underscored this change, as did the darker tone of some independent publishers such as First Comics, Dark Horse Comics, and (founded in the 1990s) Image Comics. This tendency towards darkness and nihilism was manifested in DC's production of heavily promoted comic book stories such as "A Death in the Family" in the Batman series (in which The Joker brutally murdered Batman's sidekick Robin), while at Marvel the continuing popularity of the various X-Men books led to storylines involving the genocide of superpowered "mutants" in allegorical stories about religious and ethnic persecution.

Though a speculator boom in the early 1990s temporarily increased specialty store sales — collectors "invested" in multiple copies of a single comic to sell at a profit later — these booms ended in a collectibles glut, and comic sales declined sharply in the mid-1990s, leading to the demise of many hundreds of stores. In the 2000s, fewer comics sell in North America than at any time in their publishing history.[citation needed]

The large superhero-oriented publishers like Marvel and DC are still often referred to as the "mainstream" of comics and are still considered a mass medium like in previous decades.

While the actual publications are no longer as widespread, however, licensing and merchandising have made many comic-book characters, aside from such perennials as Superman and Batman, more widely known to the general public than ever[citation needed] . In particular, several movies and videogames based on comic-book characters have been released, and such heavily promoted events as Spider-Man's wedding, the death of Superman, and the death of Captain America received widespread media coverage.

Prestige format[]

Prestige format comic books are typically longer than standard comic books, typically being of between 48 and 72 pages, and printed on glossy paper with a spine and card stock cover. The format was first used by DC on Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. The success of this work led to the establishment of the format, and it is now used generally to showcase works by big name creators or to spotlight significant storylines.

These storylines can be serialized over a limited number of issues, or can be stand-alone. Stand-alone works published in the form, such as Batman: The Killing Joke, are sometimes referred toTemplate:By whom either as graphic novels or novellas.

Independent and alternative comics[]

- Main article: Alternative comics

Comic specialty stores did help encourage several waves of independent-produced comics, beginning in the mid-1970s. The first of these was generally referred to as "independent" or "alternative" comics; some of these, such as Big Apple Comix, continued somewhat in the tradition of underground comics, while others, such as Star Reach, resembled the output of mainstream publishers in format and genre but were published by smaller artist-owned ventures or by a single artist; a few (notably RAW) represented experimental attempts to bring comics closer to the world of fine art.

The "small press" scene continued to grow and diversify, with a number of small publishers in the 1990s changing the format and distribution of their books to more closely resemble non-comics publishing. The "minicomics" form, an extremely informal version of self-publishing, arose in the 1980s and became increasingly popular among artists in the 1990s, despite reaching an even more limited audience than the small press. "Art comics" has sometimes been usedTemplate:By whom as a general term for alternative, small-press, or minicomic artists working outside of mainstream traditions. Publishers and artists working in all of these forms stated a desire to refine comics further as an art form.

Artist recognition[]

Some comic books have gained recognition and earned their creators awards from outside the genre. Thus Art Spiegelman's Maus won a Pulitzer Prize, and an issue of Neil Gaiman's The Sandman won the World Fantasy Award for "Best Short Story". Though not a comic book itself, Michael Chabon's comic-book themed The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Popular interest in superheroes increased with the success of feature films such as X-Men (2000) and Spider-Man (2002). To capitalize on this interest, comics publishers launched concerted promotional efforts such as Free Comic Book Day (first held on May 5, 2002). In addition, filmed adaptations of non-superhero comic books, such as Ghost World, A History of Violence, Road to Perdition, and American Splendor, followed.

Production[]

Template:Original research Mainstream American comic books generally come to be collaboration. Generally, a writer/scripter/plotter will outline the whole story and act as a core of the storytelling process. (At EC, Al Feldstein and Bill Gaines came up with a new story every working day for over five years - an accomplishment unequaled in the field.)

The penciller is the first step in rendering the story in visual form and may require several steps of feedback with the writer. These artists are concerned with layout (positions and vantages on scenes) to showcase steps in the plot. In earlier generations it was more common for artists to use a loose pencilling approach, in which the penciller does not take much care to reduce the vagaries of the pencil art, leaving it to the inker to interpret the penciller's intent and render the art in a more finished state.

Today many pencillers prefer to create very meticulously detailed pages, which indicate in pencil every nuance that they expect to see in the inked art - a technique known as "tight pencilling". Because the inking and the pencilling align so closely there are strong cross influences.

Then the colorist comes into the picture - with the responsibility for adding color to the black-and-white (possibly shaded) line-art. Almost all comic books are rendered in color and have been for much of the history of comic books. Sometimes color is not added for specific effect or when production resources don't allow for a colorist. A colorist also can add to or shift the emphasis of a page of comic art—the penciller laid out the basic scene—the inker emphasizes the depth and drama of the edges of things and their weight on the page, and the colorist can further emphasize what draws the eye and adds or subtracts to the realism of the scene.

Finally the letterer renders what needs to be said on a page of art for the story: dialogue and the content of signs or print (if shown). This may seem like an easy job, but the right use of fonts, letter sizes, and layout of the words inside the balloons all contribute to the impact of the art. A good letterer has good calligraphy skills, and a great letterer has as much to do with the quality of the comic as the writer, penciller, inker, or colorist

However, most independent works leave all of the art to one person, or sometimes the entire work is the result of one person.

The superhero and other genres[]

- Main article: Superhero

Superhero dramatic-adventure and science-fiction stories have dominated American comic books for most of the medium's history. Before the 1960s the comic-book format featured many genres, including humor, Westerns, romance, horror, military fiction, crime fiction, biography, and adaptations of classic literature. Non-superhero comics have continued to exist as niche publishing, with humor titles, such as those from Archie Comics and Bongo Comics, the most visible alternatives. DC's Vertigo imprint publishes a wide range of non-superhero series, while originally heavily supernatural or fantastic (currently limited mainly to Hellblazer, House of Mystery, Madame Xanadu, and Fables--all but the latter having some connection to the DC Universe), more of their comics have been crime or music oriented over the years.

Pricing[]

Timing varies slightly by publisher, as not all publishers changed prices at the same time. (Data samples taken from X-Men, Action Comics, and Avengers cover-price listings in ComicBase 10 Archive Edition.) Typical prices of a new, standard-size, mainstream American comic book, in US$:

|

|

See also[]

Template:Portalbox

- List of films based on English-language comics

- List of years in comics

- List of comic book publishing companies

Footnotes[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Coville, Jamie. The History of Comic Books: Introduction and "The Platinum Age 1897 - 1938", TheComicBooks.com, n.d. Archive of original page published at defunct site CollectorTimes.com

- ↑ Himmelweit, Hilde et al. Television and the Child (Oxford University Press, London, 1958) p.36

- ↑ U.S. Library of Congress, "American Treasures of the Library of Congress" exhibition

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Goulart, Ron. Comic Book Encyclopedia (Harper Entertainment, New York, 2004)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Brown, Mitchell. "The 100 Greatest Comic Books of the 20th Century: Funnies on Parade" (Internet archive link)

- ↑ "Famous Funnies- Carnival of Comics". The Grand Comics Database. http://www.comics.org/details.lasso?id=75. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ↑ Daniels, Les. DC Comics: 60 Years of the World's Favorite Comic Book Heroes (Little Brown, 1995).

- ↑ Daniels Template:Page needed

- ↑ Willits, Malcolm. "Interview with George Sherman". Vanguard 1968, reprinted in Duckburg Times #12 (1981).

- ↑ An example of the sensational coverage of comics in the mass media is Confidential File: Horror Comic Books!, broadcast October 9, 1955 on Los Angeles television station KTTV.

- ↑ History of Comics-Bronze AgeTemplate:Dead link

References[]

- All in Color for a Dime by Dick Lupoff & Don Thompson ISBN 0-87341-498-5

- The Comic Book Makers by Joe Simon with Jim Simon ISBN 1-887591-35-4

- DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World's Favorite Comic Book Heroes by Les Daniels ISBN 0-8212-2076-4

- The Great Comic Book Heroes by Jules Feiffer ISBN 1-56097-501-6

- Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics by Les Daniels ISBN 0-8109-3821-9

- Masters of Imagination: The Comic Book Artists Hall of Fame by Mike Benton ISBN 0-87833-859-4

- The Official Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide by Robert Overstreet—Edition #35 ISBN 0-375-72107-X

- The Steranko History of Comics, Vol. 1 & 2, by James Steranko—Vol. 1 ISBN 0-517-50188-0

- CBW Comic History: The Early Years...1896 to 1937, Part II

- Coville, Jamie. The History of Comic Books: Introduction and "The Platinum Age 1897 - 1938", TheComicBooks.com, n.d. Originally published at defunct site CollectorTimes.com.

- The Greatest Comics: New Fun #1

- Don Markstein's Toonopedia: Dell Comics

Further reading[]

- Garrett, Greg, Holy Superheroes! Exploring the Sacred in Comics, Graphic Novels, and Film, Lousville (Kentucky): Westminster John Knox Press, 2008. (Translated into Spanish: La fe de los superhéroes. Descubrir lo religioso en los «comics» y en las películas, Sal Terrae, Santander 2009.)

External links[]

- The Comics Buyer's Guide's "Comic Book Sales Charts and Sales Analysis Pages"

- The pictures that horrified America CNN

- A History of the Comic Book (American comic book history only)